Now that 2012 is over, it is time to update a comparison of simulations and observations of global mean temperatures.

[UPDATE (17/03/13): David Rose has written an article in the Mail on Sunday which, by eye, seems to use the top left panel from the figure below, but without mention of its original source. In the article David Rose suggests that this figure proves that the forecasts are wrong. This is incorrect – the last decade is interesting and I have discussed these issues previously (as have many others) and I have even co-authored a published article about the most sensitive simulations being less likely. David also incorrectly suggests that the shaded ranges shown are 75% and 95% certainty. As labelled below, they are actually the 25-75% and 5-95% ranges, so 50% and 90% certainty respectively.]

[UPDATE (21/03/13): Mail on Sunday acknowledge that Climate Lab Book figure was used & redrawn and apologise for lack of credit in article update.]

[UPDATE (16/04/13): The Economist also used a version of the figure below in an article on climate sensitivity.]

[UPDATE (17/04/13): Two new published papers suggest that deep ocean warming is the reason why the surface temperature has not warmed so rapidly in the last 15 years: Balmaseda et al. & Guemas et al.]

[UPDATE (25/04/13): The graph below has now been used in evidence to the US House of Representatives by Judith Curry.]

[UPDATE (20/05/13): The most recent appearance of this now infamous graph was on CNBC, wrongly attributed to ‘Mail Online’.]

[UPDATE (29/05/13): A complete update to this post is now available.]

Previously I compared the CMIP5 simulations (performed over the past couple of years) and observations attempting to consider the effects of the relative availability of observations. Now that we have some new observations (HadCRUT4 up to 2012) an update can be made. (Note that RealClimate have also done something similar).

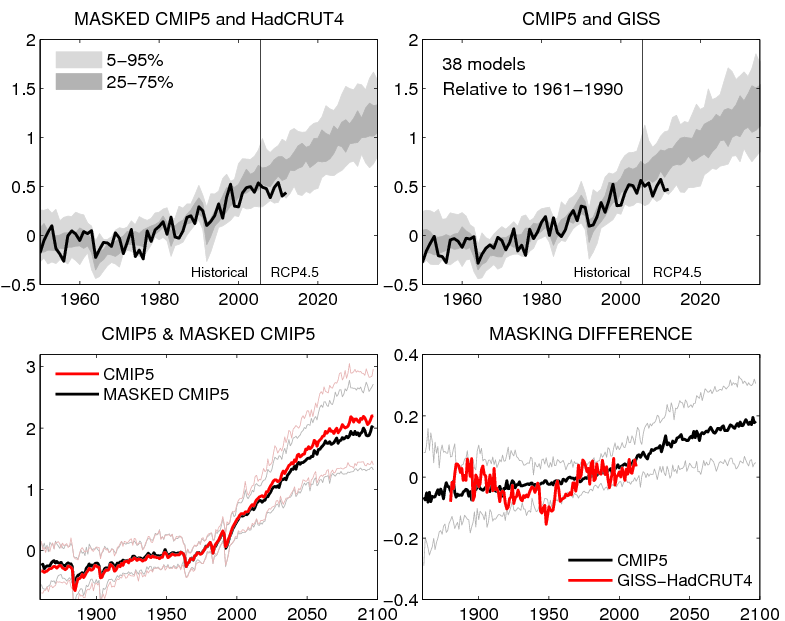

The figure below (top row) shows the comparison of observations (HadCRUT4 & GISS) with the CMIP5 simulations, but masking the simulations with the HadCRUT4 observational mask for that comparison. The bottom row shows the effect of the masking on the simulated temperatures, which continues to grow into the future (assuming the current observational mask).

MASKING UPDATE: Paul Matthews suggested that I needed to explain masking a bit more. HadCRUT4 only uses available observations of temperature, and there are many missing regions. Therefore the comparison is only done using model data where observations exist that particular month (see here for more details). GISS observations however are interpolated and fill in the observational gaps to create a complete dataset which does not need masking.

Can you confirm what those top two charts appear to display. That within the 5 year ex ante forecast period you have plotted observations are already at the 5% confidence limit.

Geckko – yes the observations are at the lower edge of the projected range – several possible reasons – see this post.

Ed.

The charts also show the observations at the 5% CL at least half a dozen times in the historical record since 1950. I will guess this indicates a reasonable expectation of divergence, but Ed’s list of reasons must all be considered.

Always a pity we only have one planet to get observational data from…

Pete, While what you say is true, it is also true that the last 10 years or so is the longest period shown in which the observations are in the light grey band. Watch out for cherry picking!

Hi Ed,

I wonder how good I am at interpreting such data. I have a sneaky suspicion that the underlying statistic I am trying to judge visually is deceptive.

What I should like to know is the cumulative distribution of the models time to breech some specified CI value. E.G. what proportion of the models have at some point diverged from their ensemble mean at least as far as the temperature record has.

I don’t know the answer to that but it might be a surprisingly high proportion.

The way the data is inevitable presented (in instalments) risks it suffering from a conditional stopping bias, i.e. watching for the record to breech and thinking “aha”.

The other query would be as to whether the temperature record is exchangeable with the ensemble, particularly with respect to variance. If we have doubts about that (which I do) then the CIs will be inappropriate. That is specialised territory that I do not really comprehend. I am not sure many of the laity do.

I think there is another issue that may await us. Suggesting that x years is not significant but x+n would be. Which can lead to a failure to anticipate the already likely as x+n is not conditional on x having already happened, which by definition it has. Which in turn can make it seem that it has been shown to be doubly significant.

Many thanks

Alex

Hi Alex,

We have a paper appearing shortly which will look at the ‘reliability’ of the historical simulations, i.e. do the observed trends appear outside the ensemble spread more often than expected which addresses some of these points.

I agree that there are potential biases from seeing the data first.

cheers,

Ed.

A couple of points.

1) Are my eyes deceiving me. The ensemble seems to a do a fairly good job of matching the rises and dips in the observation data since 1998 (particularly Hadcrut4). But my understanding is the model runs don’t try to match the real world ENSO history. So the ensemble got lucky with the annual variability or it’s just my eyes looking for patterns?

2) The “relative to 1961-1990” means that the observations and ensembles are encouraged to match each other for that period? If that’s the case then if you were inclined to look for divergence between the two date sets you would only really have had 22 years in which that divergence might have developed?

Hi HR,

1) The historical simulations have volcanic eruptions, so should show similar dips after El Chichon (1983) and Pinatubo (1991) for instance. The rest is more by chance if there is any correspondence with interannual variability.

2) Yes, the ensembles are matched over the 1961-1990 period, so there have been 22 years in which differences may have developed.

Ed.

I think he means the outer edges are 75% and 95% and readers would interpret it that way. So, I don’t see a problem with what he said. (If that’s not what you mean, you are being confusing.)

We can quibble about what Rose’s claim models are “wrong” means. It’s looks like the ensemble is biased high by inclusion of some models that are clearly warm without including any that are cold. But Rose is unequivocally wrong in this:

Neither your graph nor the version in the IPCC version show the world “is soon set to be cooler”!

Thanks Lucia – my reading is that David is incorrect but I agree that could be a quibble. Agree that he is certainly wrong to suggest that the figure shows a future cooling!

Cheers,

Ed.

Ed

It was Bellamy that said cooling, not Rose.

Oops – sorry. Thanks!

Well.. Rose isn’t exactly nuanced, is he? Hypothetically “models are wrong” could mean:

1) 1 model in the ensemble is wrong.

2) The mean for projection is wrong.

3) Some models are wrong.

And you can’t tell from what he wrote which he meant. Monckton’s writing shares this interesting ‘feature’ and so appears ‘strategically ambiguous’.

I still don’t know why you and RC don’t show color for each model when making your error bands so people can *see* that spread isn’t “weather”. I’m under the impression Gavin’s “point” is that we shouldn’t care the spread isn’t “weather” because — for some mysterious reason– we are only supposed to care whether the observations fall inside the larger-than-weather spread of all weather + structural uncertainty of forecast. But that would be a rather bizarre limitation since what we ought to want to know is what range of forecasts are consistent with *earth weather* not merely “does trend fall inside spread of all models in all weather”. It does — because the models with the lowest projected warming aren’t inconsistent with the data.

It’s only the ones with the fastest projected warming that are inconsistent with the data. That is: Only a subset of models that we all anticipate will be accepted for inclusion in the ensemble to of the AR5 can be diagnosed as “wrong” in the sense that their projections of over all warming are inconsistent with observed warming.

FWIW: I predict the graph used in the final AR5 will fail to use color in a way that would permit a reader to easily detect that this subset is wrong. And I don’t think this is because people don’t know how to use color when they want to use it. I think it is “strategic ambiguity” which will be decided on collectively. Y

I also predict that “some” will continue to complain that people call models wrong if their forecast is inconsistent with observations given an estimate of the spread of weather in one model– or spread of weather on earth.

Mind you– that’s not Rose’s point. I don’t think he knows enough to understand the distinction. He’s just showing your graph.

But at least you your co-authors adjusted the best estimate of the forecast downward in your paper– which seems the right thing to do even if it’s a bit much not to admit… well.. the reason it has to be done because the raw AOGCM forecasts are wrong— as in “biased high”.

“GISS observations however are interpolated and fill in the observational gaps to create a complete dataset which does not need masking.”

How does this make it any better? As far as I can tell, it means that models will be compared with observations + estimates. The problem being in the assumptions made by the ‘interpolation’ of missing data. When other people have interpolated data, it has drawn criticism and complaints.

Thanks Ben – I don’t think I necessarily suggest that interpolation is better – it is a choice with pros and cons. Just means that comparisons need to be done carefully!

Cheers,

Ed.

Don’t let people find out that the outcome of science is sensitive to choices!

It’s not clear from the update what the pros/cons of the two datasets are. Thus it appears that you’re saying that the GISS datasets, interpolations notwithstanding, sheds more light on something (we know not what). So for example, do we trade off the need for masking with a loss of certainty/confidence? You should say so. It’s also not immediately apparent what is happening between the different charts — a problem which is made worse by the rows using different scales on both axes.

Sadly, I think the need for more exposition here is because of the expectations that are on science. For instance, some are suggesting that prematurely over-interpreting the top left graph should incur the intervention of state regulators.

That might not be a debate you want to get into. And why would you? But the problem is that debate is the environment which your research and this blog feeds into, and hopefully informs.

Ed.

Where did your update go?

People. Including those influentially in the media, have read that and formed conclusions about Rose. Will you tell them you have removed it?

Hi Barry – update was accidentally removed – now restored!

Thanks,

Ed.

Dear Hawkins,

I have sent you four papers on the prediction of the current warming slowdown made in ten years ago. This prediction can also be found from my four Chinese books. Extreme weather events are result of heating contrast but not the global warming or cooling.

Is the point of your new update to try to communicate that Rose or others should use two sided tests and so convert from 1 sided to two sided?

If you want to communicate that point clearly, you might consider actually using the words “two sided” “and one sided” in your update. Because, your figures do say the bounds are 5% and 95%, and — in fact– the 95% trace is the 95% trace if a test is one sided. If you want to make the point that Rose (or others) should understand the difference and somehow “know” that the test should be two sided even though your figures shows 1 sided intervals, you should make the point about the conversion directly. Don’t leave everyone who knows something about statistics a scratching their heads until they guess what point you might be trying to make.

Hi Lucia,

I was never implying or using any particular test of consistency – the distribution of the model simulations are just shown as they are and compared with the observations.

Cheers,

Ed.

Ed–

I didn’t say you suggested a type of test. In fact, what I’m saying is your failure to mention types of tests in your update makes it less than clarifying– and rather more wrong that right. I’m saying owing to missing detail your update is confusing and sounds bizarre.

But your update now says the 95% confidence intervals is not the 95% confidence intervals but rather the 90%. But the 95% confidence interval is a 95% percent confidence interval. So the whole update sound confusing. You can’t be entirely correct when you say it’s “not” a 95% confidence interval, but “really” a 90% confidence interval unless you explain the difference. Explaining the difference requires discussing the difference– 1 sided vs. 2 sided. So it’s your failure to explain this while converting is the problem.

FWIW: I reread rose and in the body he does use them as two sided– so he does use 95% ‘onesided’ in a ‘twosided’ way and so should have converted. But if you want to be clear on what went wrong, I think you need to actually say it in the update.

I would greatly appreciate some clarity on why it is neccessary to use different ranges in explaining probability around the mean in displaying climate models/ranges around ensemble mean etc.

Not being a statistician I am used to a 95% test being appliedin medical papers, and distributions /CIs displayed like this.

Even though I thought that was what Rose meant and was implying 75 and 95 percent around the ensemble mean I am constantly confused by other displays eg

this Met Office page where one line shows 10-90% and seems to interchange with 5-95% on the same page

http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/climate/seasonal-to-decadal/long-range/decadal-fc

Why is this necessary?

Different ranges are chosen to illustrate more aspects of the distribution than just the median and 5-95% say. The distribution may be skewed, i.e. wider on one side than the other, or have a different shape which showing different ranges illustrates.

Cheers,

Ed.

Thanks Ed

Don’t forget that there is still an energy imbalance and that approximately 90.3% of the Earth’s added heat is going into the ocean. The World Ocean is about 71% of Earth’s surface so the warming is substantial no matter what the land/atmosphere temperature shows.

Why don;t the models account for the heat going into the ocean?

Don’t the models account for the heat going into the ocean?

Update 17.4.2013 states:

“Two new published papers suggest that deep ocean warming is the reason why the surface temperature has not warmed so rapidly in the last 15 years”

What these papers do not explain is why the models used by the IPCC (et al.) failed to predict the deep ocean warming. The heat capacity of water is well known, so why was this not taken into account?

Also from the abstracts it is not possible to determine a mechanism by which this deep ocean warming is occurring. Any enlightenment would be welcome.

Hi Matt,

The Guemas et al. paper demonstrated that their model predicted the slowdown in surface warming, and deeper ocean warming, in hindsight. This type of decadal prediction which is more like a long term weather forecast, where the initial state of the ocean matters, is very new (the first one was 2007), is still very experimental, and therefore was not available to be run in real time for the slowdown.

If you email me I might be able to provide copies of the full papers, and we can discuss further.

cheers,

Ed.